Additional notes to the

onlie begetter controversy.

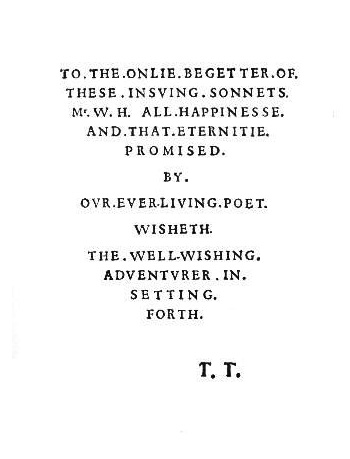

Another important echo, which has rarely been discussed, is the identification of the youth with Christ, an echo which is apparent here, and leads me to suspect that the dedication is really the work of Shakespeare. For the ONLIE. BEGETTER. by an easy transformation becomes the 'only begotten' of the Gospels, and the youth, as well as the poet, by a strange transubstantiation or transmutation, both become Christ-like figures. In the Elizabethan Book of Common Prayer, in the Communion Service, or, to give it its full title from the BCP:

the phrase is used three times, and I give the details below:

And the Epistle and Gospel being ended shall be said the Creed.

I BELEVE in one God, the father almighty maker of heaven and earthe, and of all thynges visible and invisible: And in one Lorde Jesu Christe, the onely begotten sonne of GOD, begotten of his father before al worldes, god of God, lyghte of lyghte, verye God of verye God, gotten, not made, beynge of one substance wyth the father, by whome all thinges were made, who for us men, and for our salvacion came doune from heaven, and was incarnate by the holy Ghoste, of the Virgine Mary, and was made man, and was crucified also for us, under Poncius Pilate.

............

Then shall the priest also say.

Hear what comfortable words our Savior Christ saith, to all that truly turn to him.

COME unto me

all that travaile and be heavy

laden, and I shal refreshe you. So God loved the world that he gave his

onely

begotten

sonne, to thende that al that beleve in him, should not perishe but

have

life everlastyng.

.............

Then shall be said or sung.

GLORYE be to God on hyghe. And in earthe peace, good wyll towardes men. We prayse thee, we blesse thee, we worshyppe thee, we glorifye thee, wee geve thanckes to thee, for thy greate glorye. O Lorde God, heavenlye Kynge, God the father Almightie. O Lorde the onely begotten Sonne Jesu Christ.

(These quotations are from the 1559 version of the Book of Common Prayer, the full text of which is available on line. To access it use this link ). I have cited the BCP rather than the opening of St. John's Gospel, which is the more obvious starting point, because it is more probable that Elizabethans would be familiar with what was always being read in their churches than with remembrance of any private reading of the Bible.

Bearing in mind the latent religious references in many of the sonnets, most notably in 34 (St. Peter's denial of Christ), 52 (the Beatitudes), 88 (the revilement by the Jews), 90 (abandonement on the cross), 105 (idolatrous love; the Holy Trinity), 108 (hallowed be thy name), 109 (repentance, baptism), 110 (world without end), 111 (drinking of vinegar), 125 (oblation of himself as a loving sacrifice), this being only a partial list, it is almost unthinkable that the writer was unaware of the potential contact with New Testament reference, or indeed that he was unfamiliar with the Communion Service readings. One other striking echo also occurs in the sonnets, drawn from the very same passage of the Communion Service shown above which includes the 'only begotten', for the opening line of Sonnet 53 seems to parallel the description of Christ there given:

What is your substance, whereof are you made, 53

beynge of one substance wyth the father, by whome all thinges were made,

the latter being taken from the first BCP excerpt above. There was also appointed to be spoken on The Feast of the Trinity the following:

O Lord, almighty and everlasting God, which art one God, one Lord, not one only person, but three persons in one substance: for that which we believe of the glory of the Father, the same we believe of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, without any difference or inequality

Sonnet 53 is read and explained usually in terms of Neo-Platonic philosophy, but a more immediate key to its meaning must surely be the BCP passage above. The implication is that the youth is, or might be seen as, a Christ like figure. Is he of the same substance as the Father, that millions of strange shadows (angels?) on him tend and do his bidding? Yet his substance is sufficient to give light to all the world, though being only one, single, yet sharing the mystery of the disparate oneness of the Trinity.

It is no doubt

strange to a modern scientific ear

that so much theological significance should be attached to the single

word

'substance' but OED gives as its primary meaning

1. Essential

nature, essence;

esp. Theol., with regard to the being of God, the divine nature or

essence

in respect of which the three Persons of the Trinity are one.

and gives the

following examples:

1450–1530 Myrr. Our

Ladye 4 The

glory of the

blessyd endeles Trinite in onehed of substaunce and of Godhede. 1526 Pilgr.

Perf. (W. de W. 1531)

197

The pure

substaunce of god in his owne nature & deite.

1585

Dyer

Prayse of Nothing Writ. (Grosart)

77 That substance, which we

communicate with Angels,

being created of nothing.

1597

Hooker Eccl.

Pol. v. lii. §3 In Christ

therefore

God and man there is a two-folde substance, not a two-folde person,

because

one person extinguisheth an other, whereas one nature cannot in another

become extinct.

c1610

Women

Saints 173/11 [Arius] affirming

the Sonne of god to be of

inferiour

substance to his Father.

In

addition there is:

3.c. with

reference to the

doctrine of the Real Presence in the Eucharist.

with

the following examples:

1546

Gardiner Detect. Deuils Sophistrie 14b, The

substaunce of bred,

beyng conuerted into the naturall bodely

substaunce of our sauioure [printed souioure] Christe. 1565 Harding Answ.

Jewel 162b, In this Sacrament

after

consecration there remayneth+onely the accidentes and shewes, without

the

substance of bread and wyne. 1597 Hooker Eccl. Pol. v.

lxvii. §10 How the wordes of

Christ

commaunding vs to eate must needes importe

that as hee hath coupled the substance of his fleshe and the substance

of

bread together, so we together should receiue both.

It is

clear therefore that there are strong

emotive, religious and philological links between the use of the word

substance

as Shakespeare used it in sonnet 53 and its immediate reference to the

divine

nature, and particularly to how that nature revealed itself in the Holy

Trinity and in the mystery of transubstantiation (change of substance,

essence)

in the Communion Service. For it is from the communion service that the

echo is generated originally, rather than directly from the Gospels. As

the sonnet progresses, the classical references obtrude, which throw

the

reader off the scent, and they bring to the forefront a world of

mythological

figures with imagery that possibly relates to neo-Platonism, but which

is

not necessarily present in the opening lines. However the return to

more

natural imagery in the third quatrain takes us back once more to

religious

themes, the lilies of the field, Christ the giver, blessedness in the

beatitudes

(the meek, the poor, the merciful, the many shapes of blessedness).

Finally

all is rounded off with external grace and the solid foundation of the

constant

Trinity, you, none you, and you. Constancy is not specifically

highlighted

by OED as having a religious ambience, and the examples are few:

a1600 Hooker (J.), The laws of God+of a different constitution from the former, in respect of the one's constancy, and the mutability of the other.

But constancy and the Trinity are recalled in another famous sonnet about the beloved and the Holy Trinity, 105:

Let not my

love be called idolatry,

Nor my beloved as an idol show,

in which reference is made to the beautiful youth as

Still

constant in a wondrous excellence;

Therefore my verse to constancy confined,

One thing expressing, leaves out difference. 105.6-8.

The claim of constancy here in the couplet of 53 is therefore an answer to the question of line 1, that the beloved does indeed have divine qualities. Constancy is the essence of the Trinity, the three godheads are in fact one in substance, they are constant and unchanging, they express one thing, they leave aside difference. (See the excerpt from the Feast of the Trinity reading above). These references (in 105) are in fact accepted by most commentators, for they are fairly obvious and one does not have to delve too deeply into scripture or theological texts to unravel them.

The importance of the

above interpretation of 53

for the argument here presented, is that it identifies the beloved with

God, a fairly close identification with the Son as begotten by the

Father.

Presumably the Father is the only begetter of his only begotten Son. .

For

the opening line of the sonnet ties in with

beynge of one substance wyth the father, by whome all thinges were made,

which occurs in the Communion Service in close proximity to the first

reference

to 'the only begotten'. This echo is taken up in what have always been

assumed

to be Thorpe's words in the dedication, 'To the onlie begetter of these

insuing sonnets', words which I suspect were in fact written by

Shakespeare.

For those who have doubts that these sonnets are imbued with religious hints and references, rather than say merely having a philosophical basis, and having strong links with neo-Platonism, it is worth bearing in mind that the interpretation of

Let me not

to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments 116.

which is universally accepted as relating to words from the marriage service given in the BCP, hinges mainly on the single word impediments, and of course the fact that the word (in the singular) occurs in the Marriage Service. In 53 the key words are substance and made, but it is significant that the words come from the Communion Service, the offering or oblation of the body and blood of Christ through the sacrament of the Eucharist. The language of the sonnets elsewhere confirms the imporatnce of oblation, for in 125 the beloved giving himself as an oblation does so as

But mutual render, only me for thee. 125.

The oblation is the sacrifice on the Cross, the ultimate sacrifice of love, and by a transformation in the poet's mind, the offering of himself becomes a sort of Eucharist to the beloved, as also in A Lover's Complaint, when the treacherous youth offers the loves and love tokens of all his former conquests as an oblation to the maiden. (LC.223.)

I have laboured these points, and emphasised the deeply religious flavour of some of the sonnets mainly to show that the religious doctrines and their suggestiveness is fairly evident when the connections are made between the appropriate places in the Sonnets and the original texts read in the Churches. I propose that these suggestions and echoes, although they may not have been consciously included, in the sense that in the writing of poetry what is or is not conscious may not be a meaningful distinction to make, were nevertheless not removed, but deliberately retained because of their power to enhance the record of the experience of loving.

I am not hastening to suggest that Shakespeare was being frivolously blasphemous in using this or any of the other biblical echoes sprinkled throughout the sonnets. Or indeed that the sonnets are predominantly religious in tone. For they are not, they are primarily about the experience of loving. What I do however suspect, because of the frequency and intensity of the religious echoes, is that the reference here in the dedication is not an unconscious one, but deliberate, and serves to echo and enhance the thematic content of the main work. The beloved is like the beauteous transfigured Christ, the lover is in many instances like the suffering and sacrificed Christ, and the two are one flesh, their hearts are interchangeable. It might be objected that any work treading so perilously close to parodying religious themes would be in danger of condemnation and burning, and the author might fear for his life. Had the Sonnets been a work of religious doctrine, it would no doubt have been closely scrutinised. Being mere sonnets, they could be passed on the nod, and no one would look too deeply into them, or at least nobody in authority would, and unless they became hugely popular, they would probably never raise an eyebrow, for the Stationer's Office, which would have had other far more weighty matters to consider, could be considered to have done its job well. Yet it is interesting that one early reader has recorded his/her comment after the final sonnet 'What a heap of wretched Infidel Stuff'. (Quoted in KDJ Intro. p. 169). Whether the early readers of Shakespeare's sonnets, who found them 'sugred', also found them blasphemous, is not recorded. (The sonnets that they had the opportunity to read may however not be the ones that we have). And it must be admitted that one has to have an ear attuned to these matters, for the mind tends to listen more to beauteous comparisons and felicity of language, rather than to possibly obscure religious references. Nevertheless the textual echoes are quite striking. And it is a more probable derivation than is the relatively recent suggestion (1987) that ever-living (see below) is an epithet used mostly of God, and therefore the ever-living poet probably in this case refers to God rather than to Shakespeare.

I have not discovered yet if the link between 53 and the passage cited above, or indeed the link between ONLIE. BEGETTER and the only begotten Son has been previously noted. It is possible that it has been scrutinised and subsequently dismissed. Yet given the dense texture of the Sonnets, the interweaving in them of so many disparate elements, and the frequent and haunting echoes of the well known New Testament themes, we should look again at these references and acknowledge that they tie in perfectly with the thematic content of the Sonnets - that love is eternal and absolute; that human love partakes of the divine; that even if the beloved object is imperfect (as in this case indeed he is, being a man instead of a woman, and being conceited and frivolous to boot), yet love makes no distinction; that even as divine love was willing to sacrifice all for imperfect and sinful mankind, the creature who was really not worthy of such suffering, human love also can make the same sacrifice.

It is almost unthinkable that Thorpe himself with a full realisation of their significance could have chosen these words, for as a publisher he would hardly have wished to have laid himself open to a capital charge. But, as presented to him by Shakespeare, and with full knowledge of their gentle secular irony, as distinct from their religious import, it would have been an entirely different matter.

The possibility (to my mind the probability) that Shakespeare wrote the dedication, does of course throw a new light on the Sonnets, for it would no longer be possible for us to consider them as pirated, or that the author wished them to be suppressed, or that he had no hand in their publication, or that they were only written for private circulation, or that he considered them to be derogatory to his reputation. These are important considerations for any future survey of their themes and history.

Whether or not in the cold light of reason one agrees with these loving postures of the poet (as outlined above), is another matter. But it is noticeable that the main theme is repeated in A Lover's Complaint, where the maid acknowledges her fault, but also acknowledges the impossibility of responding to the precepts of love in any other way. Her language also is couched in religious terms (pervert, reconciled), and in the final stanza she concludes, with no dissenting voice being offered by the listening poet or sympathetic shepherd, that all the youth's beauties, if once again presented to her in the same way

Would yet

again betray the fore-betrayed,

And new pervert a reconciled maid. LC. 328-9.

That is, that love would once again be triumphant.