Sonnet I

From fairest creatures

we desire increase,

That thereby beauty's rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed'st thy light's flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thy self thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel:

Thou that art now the world's fresh ornament,

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And, tender churl, mak'st waste in niggarding:

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world's due, by the grave and thee.

When

forty winters shall besiege thy brow,

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty's field,

Thy youth's proud livery so gazed on now,

Will be a totter'd weed of small worth held:

Then being asked, where all thy beauty lies,

Where all the treasure of thy lusty days;

To say, within thine own deep sunken eyes,

Were an all-eating shame, and thriftless praise.

How much more praise deserv'd thy beauty's use,

If thou couldst answer 'This fair child of mine

Shall sum my count, and make my old excuse,'

Proving his beauty by succession thine!

This were to be new made when thou art old,

And see thy blood warm when thou feel'st it cold.

Look

in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest

Now is the time that face should form another;

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother.

For where is she so fair whose uneared womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond will be the tomb

Of his self-love, to stop posterity?

Thou art thy mother's glass and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime;

So thou through windows of thine age shalt see,

Despite of wrinkles, this thy golden time.

But if thou live, remembered not to be,

Die single and thine image dies with thee.

Unthrifty loveliness,

why dost thou spend

Upon thy self thy beauty's legacy?

Nature's bequest gives nothing, but doth lend,

And being frank she lends to those are free:

Then, beauteous niggard, why dost thou abuse

The bounteous largess given thee to give?

Profitless usurer, why dost thou use

So great a sum of sums, yet canst not live?

For having traffic with thy self alone,

Thou of thy self thy sweet self dost deceive:

Then how when nature calls thee to be gone,

What acceptable audit canst thou leave?

Thy unused beauty must be tombed with thee,

Which, used, lives th' executor to be.

Those hours, that with gentle work did frame

The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell,

Will play the tyrants to the very same

And that unfair which fairly doth excel;

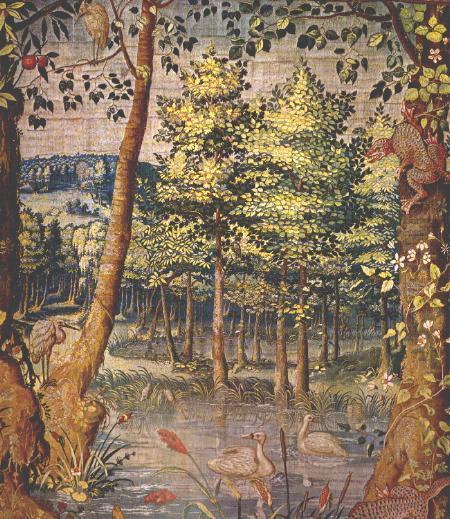

For never-resting time leads summer on

To hideous winter, and confounds him there;

Sap checked with frost, and lusty leaves quite gone,

Beauty o'er-snowed and bareness every where:

Then were not summer's distillation left,

A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass,

Beauty's effect with beauty were bereft,

Nor it, nor no remembrance what it was:

But flowers distilled, though they with winter meet,

Leese but their show; their substance still lives sweet.

Then let not winter's

ragged hand deface,

In thee thy summer, ere thou be distilled:

Make sweet some vial; treasure thou some place

With beauty's treasure ere it be self-killed.

That use is not forbidden usury,

Which happies those that pay the willing loan;

That's for thy self to breed another thee,

Or ten times happier, be it ten for one;

Ten times thy self were happier than thou art,

If ten of thine ten times refigured thee:

Then what could death do if thou shouldst depart,

Leaving thee living in posterity?

Be not self-willed, for thou art much too fair

To be death's conquest and make worms thine heir.

Lo! in the orient when

the gracious light

Lifts up his burning head, each under eye

Doth homage to his new-appearing sight,

Serving with looks his sacred majesty;

And having climbed the steep-up heavenly hill,

Resembling strong youth in his middle age,

Yet mortal looks adore his beauty still,

Attending on his golden pilgrimage:

But when from highmost pitch, with weary car,

Like feeble age, he reeleth from the day,

The eyes, 'fore duteous, now converted are

From his low tract, and look another way:

So thou, thyself outgoing in thy noon

Unlooked on diest unless thou get a son.

Music to hear, why hear'st

thou music sadly?

Sweets with sweets war not, joy delights in joy:

Why lov'st thou that which thou receiv'st not gladly,

Or else receiv'st with pleasure thine annoy?

If the true concord of well-tuned sounds,

By unions married, do offend thine ear,

They do but sweetly chide thee, who confounds

In singleness the parts that thou shouldst bear.

Mark how one string, sweet husband to another,

Strikes each in each by mutual ordering;

Resembling sire and child and happy mother,

Who, all in one, one pleasing note do sing:

Whose speechless song being many, seeming one,

Sings this to thee: 'Thou single wilt prove none.'

Is it for fear to wet

a widow's eye,

That thou consum'st thy self in single life?

Ah! if thou issueless shalt hap to die,

The world will wail thee like a makeless wife;

The world will be thy widow and still weep

That thou no form of thee hast left behind,

When every private widow well may keep

By children's eyes, her husband's shape in mind:

Look what an unthrift in the world doth spend

Shifts but his place, for still the world enjoys it;

But beauty's waste hath in the world an end,

And kept unused the user so destroys it.

No love toward others in that bosom sits

That on himself such murd'rous shame commits.

For shame deny that thou

bear'st love to any,

Who for thy self art so unprovident.

Grant, if thou wilt, thou art beloved of many,

But that thou none lov'st is most evident:

For thou art so possessed with murderous hate,

That 'gainst thy self thou stick'st not to conspire,

Seeking that beauteous roof to ruinate

Which to repair should be thy chief desire.

O! change thy thought, that I may change my mind:

Shall hate be fairer lodged than gentle love?

Be, as thy presence is, gracious and kind,

Or to thyself at least kind-hearted prove:

Make thee another self for love of me,

That beauty still may live in thine or thee.

As fast as thou shalt

wane, so fast thou grow'st

In one of thine, from that which thou departest;

And that fresh blood which youngly thou bestow'st,

Thou mayst call thine when thou from youth convertest.

Herein lives wisdom, beauty, and increase;

Without this folly, age, and cold decay:

If all were minded so, the times should cease

And threescore year would make the world away.

Let those whom nature hath not made for store,

Harsh, featureless, and rude, barrenly perish:

Look whom she best endowed, she gave the more;

Which bounteous gift thou shouldst in bounty cherish:

She carved thee for her seal, and meant thereby,

Thou shouldst print more, not let that copy die.

When I do count the clock

that tells the time,

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night;

When I behold the violet past prime,

And sable curls, all silvered o'er with white;

When lofty trees I see barren of leaves,

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd,

And summer's green all girded up in sheaves,

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard,

Then of thy beauty do I question make,

That thou among the wastes of time must go,

Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake

And die as fast as they see others grow;

And nothing 'gainst Time's scythe can make defence

Save breed, to brave him when he takes thee hence.

O! that you were your self; but, love, you are

No longer yours, than you your self here live:

Against this coming end you should prepare,

And your sweet semblance to some other give:

So should that beauty which you hold in lease

Find no determination; then you were

Yourself again, after yourself's decease,

When your sweet issue your sweet form should bear.

Who lets so fair a house fall to decay,

Which husbandry in honour might uphold,

Against the stormy gusts of winter's day

And barren rage of death's eternal cold?

O! none but unthrifts. Dear my love, you know,

You had a father: let your son say so.

Not from the stars

do I my judgement pluck;

And yet methinks I have Astronomy,

But not to tell of good or evil luck,

Of plagues, of dearths, or seasons' quality;

Nor can I fortune to brief minutes tell,

Pointing to each his thunder, rain and wind,

Or say with princes if it shall go well

By oft predict that I in heaven find:

But from thine eyes my knowledge I derive,

And, constant stars, in them I read such art

As truth and beauty shall together thrive,

If from thyself, to store thou wouldst convert;

Or else of thee this I prognosticate:

Thy end is truth's and beauty's doom and date.

When I consider every thing that grows

Holds in perfection but a little moment,

That this huge stage presenteth nought but shows

Whereon the stars in secret influence comment;

When I perceive that men as plants increase,

Cheered and checked even by the self-same sky,

Vaunt in their youthful sap, at height decrease,

And wear their brave state out of memory;

Then the conceit of this inconstant stay

Sets you most rich in youth before my sight,

Where wasteful Time debateth with decay

To change your day of youth to sullied night,

And all in war with Time for love of you,

As he takes from you, I engraft you new.

But wherefore do not you a mightier way

Make war upon this bloody tyrant, Time?

And fortify your self in your decay

With means more blessed than my barren rhyme?

Now stand you on the top of happy hours,

And many maiden gardens, yet unset,

With virtuous wish would bear you living flowers,

Much liker than your painted counterfeit:

So should the lines of life that life repair,

Which this, Time's pencil, or my pupil pen,

Neither in inward worth nor outward fair,

Can make you live your self in eyes of men.

To give away yourself, keeps yourself still,

And you must live, drawn by your own sweet skill.

Who will believe my verse

in time to come,

If it were filled with your most high deserts?

Though yet heaven knows it is but as a tomb

Which hides your life, and shows not half your parts.

If I could write the beauty of your eyes,

And in fresh numbers number all your graces,

The age to come would say 'This poet lies;

Such heavenly touches ne'er touched earthly faces.'

So should my papers, yellowed with their age,

Be scorned, like old men of less truth than tongue,

And your true rights be termed a poet's rage

And stretched metre of an antique song:

But were some child of yours alive that time,

You should live twice, in it, and in my rhyme.

Shall

I compare thee to

a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer's lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed,

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature's changing course untrimmed:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st,

Nor shall death brag thou wander'st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow'st,

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

So is it not with me as with that Muse,

Stirred by a painted beauty to his verse,

Who heaven itself for ornament doth use

And every fair with his fair doth rehearse,

Making a couplement of proud compare

With sun and moon, with earth and sea's rich gems,

With April's first-born flowers, and all things rare,

That heaven's air in this huge rondure hems.

O! let me, true in love, but truly write,

And then believe me, my love is as fair

As any mother's child, though not so bright

As those gold candles fixed in heaven's air:

Let them say more that like of hearsay well;

I will not praise that purpose not to sell.

Mine eye hath played the painter and hath steeled,

Thy beauty's form in table of my heart;

My body is the frame wherein 'tis held,

And perspective that is best painter's art.

For through the painter must you see his skill,

To find where your true image pictured lies,

Which in my bosom's shop is hanging still,

That hath his windows glazed with thine eyes.

Now see what good turns eyes for eyes have done:

Mine eyes have drawn thy shape, and thine for me

Are windows to my breast, where-through the sun

Delights to peep, to gaze therein on thee;

Yet eyes this cunning want to grace their art,

They draw but what they see, know not the heart.

Lord of my love, to whom

in vassalage

Thy merit hath my duty strongly knit,

To thee I send this written embassage,

To witness duty, not to show my wit:

Duty so great, which wit so poor as mine

May make seem bare, in wanting words to show it,

But that I hope some good conceit of thine

In thy soul's thought, all naked, will bestow it:

Till whatsoever star that guides my moving,

Points on me graciously with fair aspect,

And puts apparel on my tottered loving,

To show me worthy of thy sweet respect:

Then may I dare to boast how I do love thee;

Till then, not show my head where thou mayst prove me.

Weary with toil, I haste

me to my bed,

The dear repose for limbs with travel tired;

But then begins a journey in my head

To work my mind, when body's work's expired:

For then my thoughts--from far where I abide--

Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee,

And keep my drooping eyelids open wide,

Looking on darkness which the blind do see:

Save that my soul's imaginary sight

Presents thy shadow to my sightless view,

Which, like a jewel hung in ghastly night,

Makes black night beauteous, and her old face new.

Lo! thus, by day my limbs, by night my mind,

For thee, and for myself, no quiet find.

How can I then return

in happy plight,

That am debarred the benefit of rest?

When day's oppression is not eas'd by night,

But day by night and night by day oppressed,

And each, though enemies to either's reign,

Do in consent shake hands to torture me,

The one by toil, the other to complain

How far I toil, still farther off from thee.

I tell the day, to please him thou art bright,

And dost him grace when clouds do blot the heaven:

So flatter I the swart-complexion'd night,

When sparkling stars twire not thou gild'st the even.

But day doth daily draw my sorrows longer,

And night doth nightly make grief's length seem stronger.

When

to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought,

And with old woes new wail my dear time's waste:

Then can I drown an eye, unused to flow,

For precious friends hid in death's dateless night,

And weep afresh love's long since cancelled woe,

And moan the expense of many a vanished sight:

Then can I grieve at grievances foregone,

And heavily from woe to woe tell o'er

The sad account of fore-bemoaned moan,

Which I new pay as if not paid before.

But if the while I think on thee, dear friend,

All losses are restor'd and sorrows end.

Full many a glorious morning

have I seen

Flatter the mountain tops with sovereign eye,

Kissing with golden face the meadows green,

Gilding pale streams with heavenly alchemy;

Anon permit the basest clouds to ride

With ugly rack on his celestial face,

And from the forlorn world his visage hide,

Stealing unseen to west with this disgrace:

Even so my sun one early morn did shine,

With all triumphant splendour on my brow;

But out, alack, he was but one hour mine,

The region cloud hath mask'd him from me now.

Yet him for this my love no whit disdaineth;

Suns of the world may stain when heaven's sun staineth.

Why didst thou promise

such a beauteous day,

And make me travel forth without my cloak,

To let base clouds o'ertake me in my way,

Hiding thy bravery in their rotten smoke?

'Tis not enough that through the cloud thou break,

To dry the rain on my storm-beaten face,

For no man well of such a salve can speak,

That heals the wound, and cures not the disgrace:

Nor can thy shame give physic to my grief;

Though thou repent, yet I have still the loss:

The offender's sorrow lends but weak relief

To him that bears the strong offence's cross.

Ah! but those tears are pearl which thy love sheds,

And they are rich and ransom all ill deeds.

No more be grieved atthat which thou hast done:

Roses have thorns, and silver fountains mud:

Clouds and eclipses stain both moon and sun,

And loathsome canker lives in sweetest bud.

All men make faults, and even I in this,

Authorizing thy trespass with compare,

Myself corrupting, salving thy amiss,

Excusing thy sins more than thy sins are;

For to thy sensual fault I bring in sense,

Thy adverse party is thy advocate,

And 'gainst myself a lawful plea commence:

Such civil war is in my love and hate,

That I an accessary needs must be,

To that sweet thief which sourly robs from me.

Let me confess that we

two must be twain,

Although our undivided loves are one:

So shall those blots that do with me remain,

Without thy help, by me be borne alone.

In our two loves there is but one respect,

Though in our lives a separable spite,

Which though it alter not love's sole effect,

Yet doth it steal sweet hours from love's delight.

I may not evermore acknowledge thee,

Lest my bewailed guilt should do thee shame,

Nor thou with public kindness honour me,

Unless thou take that honour from thy name:

But do not so, I love thee in such sort,

As thou being mine, mine is thy good report.

As a decrepit father takes

delight

To see his active child do deeds of youth,

So I, made lame by Fortune's dearest spite,

Take all my comfort of thy worth and truth;

For whether beauty, birth, or wealth, or wit,

Or any of these all, or all, or more,

Entitled in thy parts, do crowned sit,

I make my love engrafted to this store:

So then I am not lame, poor, nor despised,

Whilst that this shadow doth such substance give

That I in thy abundance am sufficed,

And by a part of all thy glory live.

Look what is best, that best I wish in thee:

This wish I have; then ten times happy me!

O! how thy worth with manners may I sing,

When thou art all the better part of me?

What can mine own praise to mine own self bring?

And what is't but mine own when I praise thee?

Even for this, let us divided live,

And our dear love lose name of single one,

That by this separation I may give

That due to thee which thou deserv'st alone.

O absence! what a torment wouldst thou prove,

Were it not thy sour leisure gave sweet leave,

To entertain the time with thoughts of love,

Which time and thoughts so sweetly doth deceive,

And that thou teachest how to make one twain,

By praising him here who doth hence remain.

Take all my loves, my

love, yea take them all;

What hast thou then more than thou hadst before?

No love, my love, that thou mayst true love call;

All mine was thine, before thou hadst this more.

Then, if for my love, thou my love receivest,

I cannot blame thee, for my love thou usest;

But yet be blam'd, if thou thy self deceivest

By wilful taste of what thyself refusest.

I do forgive thy robbery, gentle thief,

Although thou steal thee all my poverty:

And yet, love knows it is a greater grief

To bear love's wrong, than hate's known injury.

Lascivious grace, in whom all ill well shows,

Kill me with spites yet we must not be foes.

Those pretty wrongs that liberty commits,

When I am sometime absent from thy heart,

Thy beauty, and thy years full well befits,

For still temptation follows where thou art.

Gentle thou art, and therefore to be won,

Beauteous thou art, therefore to be assailed;

And when a woman woos, what woman's son

Will sourly leave her till he have prevailed?

Ay me! but yet thou mightst my seat forbear,

And chide thy beauty and thy straying youth,

Who lead thee in their riot even there

Where thou art forced to break a twofold truth:

Hers by thy beauty tempting her to thee,

Thine by thy beauty being false to me.

That thou hast her it is not all my grief,

And yet it may be said I loved her dearly;

That she hath thee is of my wailing chief,

A loss in love that touches me more nearly.

Loving offenders thus I will excuse ye:

Thou dost love her, because thou know'st I love her;

And for my sake even so doth she abuse me,

Suffering my friend for my sake to approve her.

If I lose thee, my loss is my love's gain,

And losing her, my friend hath found that loss;

Both find each other, and I lose both twain,

And both for my sake lay on me this cross:

But here's the joy; my friend and I are one;

Sweet flattery! then she loves but me alone.

How careful was I when

I

took my way,

Each trifle under truest bars to thrust,

That to my use it might unused stay

From hands of falsehood, in sure wards of trust!

But thou, to whom my jewels trifles are,

Most worthy comfort, now my greatest grief,

Thou best of dearest, and mine only care,

Art left the prey of every vulgar thief.

Thee have I not locked up in any chest,

Save where thou art not, though I feel thou art,

Within the gentle closure of my breast,

From whence at pleasure thou mayst come and part;

And even thence thou wilt be stol'n I fear,

For truth proves thievish for a prize so dear.

So am I as the rich, whose blessed key,

Can bring him to his sweet up-locked treasure,

The which he will not every hour survey,

For blunting the fine point of seldom pleasure.

Therefore are feasts so solemn and so rare,

Since, seldom coming in the long year set,

Like stones of worth they thinly placed are,

Or captain jewels in the carcanet.

So is the time that keeps you as my chest,

Or as the wardrobe which the robe doth hide,

To make some special instant special-blest,

By new unfolding his imprisoned pride.

Blessed are you whose worthiness gives scope,

Being had, to triumph, being lacked, to hope.

What is your substance,

whereof are you made,

That millions of strange shadows on you tend?

Since every one hath, every one, one shade,

And you but one, can every shadow lend.

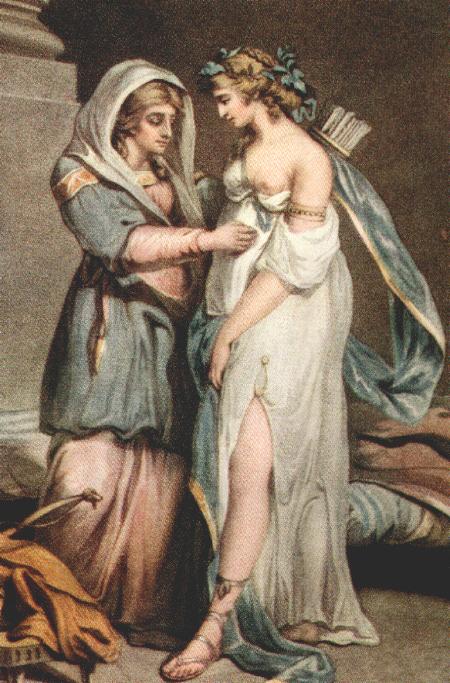

Describe Adonis, and the counterfeit

Is poorly imitated after you;

On Helen's cheek all art of beauty set,

And you in Grecian tires are painted new:

Speak of the spring, and foison of the year,

The one doth shadow of your beauty show,

The other as your bounty doth appear;

And you in every blessed shape we know.

In all external grace you have some part,

But you like none, none you, for constant heart.

O! how much more doth

beauty beauteous seem

By that sweet ornament which truth doth give.

The rose looks fair, but fairer we it deem

For that sweet odour, which doth in it live.

The canker blooms have full as deep a dye

As the perfumed tincture of the roses,

Hang on such thorns, and play as wantonly

When summer's breath their masked buds discloses:

But, for their virtue only is their show,

They live unwoo'd, and unrespected fade;

Die to themselves. Sweet roses do not so;

Of their sweet deaths are sweetest odours made:

And so of you, beauteous and lovely youth,

When that shall vade, my verse distills your truth.

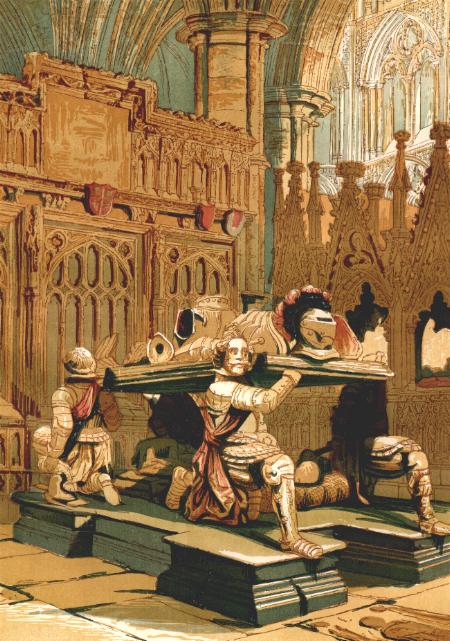

Not marble, nor the gilded

monuments

Of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme;

But you shall shine more bright in these contents

Than unswept stone, besmear'd with sluttish time.

When wasteful war shall statues overturn,

And broils root out the work of masonry,

Nor Mars his sword, nor war's quick fire shall burn

The living record of your memory.

'Gainst death, and all oblivious enmity

Shall you pace forth; your praise shall still find room

Even in the eyes of all posterity

That wear this world out to the ending doom.

So, till the judgment that yourself arise,

You live in this, and dwell in lovers' eyes.

Sweet love, renew thy

force; be it not said

Thy edge should blunter be than appetite,

Which but to-day by feeding is allayed,

To-morrow sharpened in his former might:

So, love, be thou, although to-day thou fill

Thy hungry eyes, even till they wink with fulness,

To-morrow see again, and do not kill

The spirit of love, with a perpetual dulness.

Let this sad interim like the ocean be

Which parts the shore, where two contracted new

Come daily to the banks, that when they see

Return of love, more blest may be the view;

As call it winter, which being full of care,

Makes summer's welcome, thrice more wished, more rare.

Being your slave what

should I do but tend

Upon the hours, and times of your desire?

I have no precious time at all to spend;

Nor services to do, till you require.

Nor dare I chide the world without end hour,

Whilst I, my sovereign, watch the clock for you,

Nor think the bitterness of absence sour,

When you have bid your servant once adieu;

Nor dare I question with my jealous thought

Where you may be, or your affairs suppose,

But, like a sad slave, stay and think of nought

Save, where you are, how happy you make those.

So true a fool is love, that in your will,

Though you do anything, he thinks no ill.

That god forbid, that made me first your slave,

I should in thought control your times of pleasure,

Or at your hand the account of hours to crave,

Being your vassal, bound to stay your leisure!

O! let me suffer, being at your beck,

The imprison'd absence of your liberty;

And patience, tame to sufferance, bide each check,

Without accusing you of injury.

Be where you list, your charter is so strong

That you yourself may privilege your time

To what you will; to you it doth belong

Yourself to pardon of self-doing crime.

I am to wait, though waiting so be hell,

Not blame your pleasure be it ill or well.

If there be nothing new, but that which is

Hath been before, how are our brains beguil'd,

Which labouring for invention bear amiss

The second burthen of a former child.

Oh that record could with a backward look,

Even of five hundred courses of the sun,

Show me your image in some antique book,

Since mind at first in character was done,

That I might see what the old world could say

To this composed wonder of your frame;

Whether we are mended, or where better they,

Or whether revolution be the same.

Oh sure I am the wits of former days,

To subjects worse have given admiring praise.

Like as the waves make

towards the pebbled shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end;

Each changing place with that which goes before,

In sequent toil all forwards do contend.

Nativity, once in the main of light,

Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crown'd,

Crooked eclipses 'gainst his glory fight,

And Time that gave doth now his gift confound.

Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth

And delves the parallels in beauty's brow,

Feeds on the rarities of nature's truth,

And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow:

And yet to times in hope, my verse shall stand

Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.

Is it thy will, thy image

should keep open

My heavy eyelids to the weary night?

Dost thou desire my slumbers should be broken,

While shadows like to thee do mock my sight?

Is it thy spirit that thou send'st from thee

So far from home into my deeds to pry,

To find out shames and idle hours in me,

The scope and tenor of thy jealousy?

O, no! thy love, though much, is not so great:

It is my love that keeps mine eye awake:

Mine own true love that doth my rest defeat,

To play the watchman ever for thy sake:

For thee watch I, whilst thou dost wake elsewhere,

From me far off, with others all too near.

Sin of self-love possesseth

all mine eye

And all my soul, and all my every part;

And for this sin there is no remedy,

It is so grounded inward in my heart.

Methinks no face so gracious is as mine,

No shape so true, no truth of such account;

And for myself mine own worth do define,

As I all other in all worths surmount.

But when my glass shows me myself indeed

Beated and chopp'd with tanned antiquity,

Mine own self-love quite contrary I read;

Self so self-loving were iniquity.

'Tis thee, myself, that for myself I praise,

Painting my age with beauty of thy days.

Against my love shall be as I am now,

With Time's injurious hand crushed and o'erworn;

When hours have drained his blood and filled his brow

With lines and wrinkles; when his youthful morn

Hath travelled on to age's steepy night;

And all those beauties whereof now he's king

Are vanishing, or vanished out of sight,

Stealing away the treasure of his spring;

For such a time do I now fortify

Against confounding age's cruel knife,

That he shall never cut from memory

My sweet love's beauty, though my lover's life:

His beauty shall in these black lines be seen,

And they shall live, and he in them still green.

When I have seen by Time's fell hand defaced

The rich proud cost of outworn buried age;

When sometime lofty towers I see down-razed,

And brass eternal slave to mortal rage;

When I have seen the hungry ocean gain

Advantage on the kingdom of the shore,

And the firm soil win of the watery main,

Increasing store with loss, and loss with store;

When I have seen such interchange of state,

Or state itself confounded to decay;

Ruin hath taught me thus to ruminate

That Time will come and take my love away.

This thought is as a death which cannot choose

But weep to have that which it fears to lose.

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea,

But sad mortality o'ersways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

O! how shall summer's honey breath hold out,

Against the wrackful siege of battering days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong but Time decays?

O fearful meditation! where, alack,

Shall Time's best jewel from Time's chest lie hid?

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back?

Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid?

O! none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

Tired with all these, for restful death I cry,

As to behold desert a beggar born,

And needy nothing trimm'd in jollity,

And purest faith unhappily forsworn,

And gilded honour shamefully misplaced,

And maiden virtue rudely strumpeted,

And right perfection wrongfully disgraced,

And strength by limping sway disabled

And art made tongue-tied by authority,

And folly, doctor-like, controlling skill,

And simple truth miscalled simplicity,

And captive good attending captain ill:

Tired with all these, from these would I be gone,

Save that, to die, I leave my love alone.

Ah! wherefore with infection should he live,

And with his presence grace impiety,

That sin by him advantage should achieve,

And lace itself with his society?

Why should false painting imitate his cheek,

And steal dead seeming of his living hue?

Why should poor beauty indirectly seek

Roses of shadow, since his rose is true?

Why should he live, now Nature bankrupt is,

Beggared of blood to blush through lively veins?

For she hath no exchequer now but his,

And proud of many, lives upon his gains.

O! him she stores, to show what wealth she had

In days long since, before these last so bad.

Thus is his cheek the map of days outworn,

When beauty lived and died as flowers do now,

Before these bastard signs of fair were born,

Or durst inhabit on a living brow;

Before the golden tresses of the dead,

The right of sepulchres, were shorn away,

To live a second life on second head;

Ere beauty's dead fleece made another gay:

In him those holy antique hours are seen,

Without all ornament, itself and true,

Making no summer of another's green,

Robbing no old to dress his beauty new;

And him as for a map doth Nature store,

To show false Art what beauty was of yore.

Those parts of thee that the world's eye doth view

Want nothing that the thought of hearts can mend;

All tongues, the voice of souls, give thee that due,

Uttering bare truth, even so as foes commend.

Thy outward thus with outward praise is crown'd;

But those same tongues, that give thee so thine own,

In other accents do this praise confound

By seeing farther than the eye hath shown.

They look into the beauty of thy mind,

And that in guess they measure by thy deeds;

Then, churls, their thoughts, although their eyes were kind,

To thy fair flower add the rank smell of weeds:

But why thy odour matcheth not thy show,

The soil is this, that thou dost common grow.

That thou art blamed shall not be thy defect,

For slander's mark was ever yet the fair;

The ornament of beauty is suspect,

A crow that flies in heaven's sweetest air.

So thou be good, slander doth but approve

Thy worth the greater, being wooed of time;

For canker vice the sweetest buds doth love,

And thou present'st a pure unstained prime.

Thou hast passed by the ambush of young days

Either not assailed, or victor being charged;

Yet this thy praise cannot be so thy praise,

To tie up envy, evermore enlarged,

If some suspect of ill masked not thy show,

Then thou alone kingdoms of hearts shouldst owe.

No longer mourn for me when I am dead

Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell

Give warning to the world that I am fled

From this vile world with vilest worms to dwell:

Nay, if you read this line, remember not

The hand that writ it, for I love you so,

That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot,

If thinking on me then should make you woe.

O! if, I say, you look upon this verse,

When I perhaps compounded am with clay,

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse;

But let your love even with my life decay;

Lest the wise world should look into your moan,

And mock you with me after I am gone.

O! lest the world should task you to recite

What merit lived in me, that you should love

After my death,--dear love, forget me quite,

For you in me can nothing worthy prove.

Unless you would devise some virtuous lie,

To do more for me than mine own desert,

And hang more praise upon deceased I

Than niggard truth would willingly impart:

O! lest your true love may seem false in this

That you for love speak well of me untrue,

My name be buried where my body is,

And live no more to shame nor me nor you.

For I am shamed by that which I bring forth,

And so should you, to love things nothing worth.

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou see'st the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west;

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death's second self, that seals up all in rest.

In me thou see'st the glowing of such fire,

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the death-bed, whereon it must expire,

Consumed with that which it was nourish'd by.

This thou perceiv'st, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well, which thou must leave ere long.

But be contented when that fell arrest

Without all bail shall carry me away,

My life hath in this line some interest,

Which for memorial still with thee shall stay.

When thou reviewest this, thou dost review

The very part was consecrate to thee:

The earth can have but earth, which is his due;

My spirit is thine, the better part of me:

So then thou hast but lost the dregs of life,

The prey of worms, my body being dead;

The coward conquest of a wretch's knife,

Too base of thee to be remembered.

The worth of that is that which it contains,

And that is this, and this with thee remains.

So are you to my thoughts as food to life,

Or as sweet-season'd showers are to the ground;

And for the peace of you I hold such strife

As 'twixt a miser and his wealth is found.

Now proud as an enjoyer, and anon

Doubting the filching age will steal his treasure;

Now counting best to be with you alone,

Then better'd that the world may see my pleasure:

Sometime all full with feasting on your sight,

And by and by clean starved for a look;

Possessing or pursuing no delight

Save what is had, or must from you be took.

Thus do I pine and surfeit day by day,

Or gluttoning on all, or all away.

Why is my verse so barren of new pride,

So far from variation or quick change?

Why with the time do I not glance aside

To new-found methods, and to compounds strange?

Why write I still all one, ever the same,

And keep invention in a noted weed,

That every word doth almost tell my name,

Showing their birth, and where they did proceed?

O! know sweet love I always write of you,

And you and love are still my argument;

So all my best is dressing old words new,

Spending again what is already spent:

For as the sun is daily new and old,

So is my love still telling what is told.

Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear,

Thy dial how thy precious minutes waste;

The vacant leaves thy mind's imprint will bear,

And of this book, this learning mayst thou taste.

The wrinkles which thy glass will truly show

Of mouthed graves will give thee memory;

Thou by thy dial's shady stealth mayst know

Time's thievish progress to eternity.

Look what thy memory cannot contain,

Commit to these waste blanks, and thou shalt find

Those children nursed, delivered from thy brain,

To take a new acquaintance of thy mind.

These offices, so oft as thou wilt look,

Shall profit thee and much enrich thy book.

So oft have I invoked thee for my Muse,

And found such fair assistance in my verse

As every alien pen hath got my use

And under thee their poesy disperse.

Thine eyes, that taught the dumb on high to sing

And heavy ignorance aloft to fly,

Have added feathers to the learned's wing

And given grace a double majesty.

Yet be most proud of that which I compile,

Whose influence is thine, and born of thee:

In others' works thou dost but mend the style,

And arts with thy sweet graces graced be;

But thou art all my art, and dost advance

As high as learning, my rude ignorance.

Whilst I alone did call upon thy aid,

My verse alone had all thy gentle grace;

But now my gracious numbers are decayed,

And my sick Muse doth give an other place.

I grant, sweet love, thy lovely argument

Deserves the travail of a worthier pen;

Yet what of thee thy poet doth invent

He robs thee of, and pays it thee again.

He lends thee virtue, and he stole that word

From thy behaviour; beauty doth he give,

And found it in thy cheek: he can afford

No praise to thee, but what in thee doth live.

Then thank him not for that which he doth say,

Since what he owes thee, thou thyself dost pay.

O! how I faint when I of you do write,

Knowing a better spirit doth use your name,

And in the praise thereof spends all his might,

To make me tongue-tied speaking of your fame.

But since your worth, wide as the ocean is,

The humble as the proudest sail doth bear,

My saucy bark, inferior far to his,

On your broad main doth wilfully appear.

Your shallowest help will hold me up afloat,

Whilst he upon your soundless deep doth ride;

Or, being wracked, I am a worthless boat,

He of tall building, and of goodly pride:

Then if he thrive and I be cast away,

The worst was this, my love was my decay.

Or I shall live your epitaph to make,

Or you survive when I in earth am rotten,

From hence your memory death cannot take,

Although in me each part will be forgotten.

Your name from hence immortal life shall have,

Though I, once gone, to all the world must die:

The earth can yield me but a common grave,

When you entombed in men's eyes shall lie.

Your monument shall be my gentle verse,

Which eyes not yet created shall o'er-read;

And tongues to be your being shall rehearse,

When all the breathers of this world are dead;

You still shall live, such virtue hath my pen,

Where breath most breathes, even in the mouths of men.

I grant thou wert not married to my Muse,

And therefore mayst without attaint o'erlook

The dedicated words which writers use

Of their fair subject, blessing every book.

Thou art as fair in knowledge as in hue,

Finding thy worth a limit past my praise;

And therefore art enforced to seek anew

Some fresher stamp of the time-bettering days.

And do so, love; yet when they have devised,

What strained touches rhetoric can lend,

Thou truly fair, wert truly sympathized

In true plain words, by thy true-telling friend;

And their gross painting might be better used

Where cheeks need blood; in thee it is abused.

I never saw that you did painting need,

And therefore to your fair no painting set;

I found, or thought I found, you did exceed

The barren tender of a poet's debt:

And therefore have I slept in your report,

That you yourself, being extant, well might show

How far a modern quill doth come too short,

Speaking of worth, what worth in you doth grow.

This silence for my sin you did impute,

Which shall be most my glory being dumb;

For I impair not beauty being mute,

When others would give life, and bring a tomb.

There lives more life in one of your fair eyes

Than both your poets can in praise devise.

Who is it that says most, which can say more,

Than this rich praise, that you alone, are you,

In whose confine immured is the store

Which should example where your equal grew?

Lean penury within that pen doth dwell

That to his subject lends not some small glory;

But he that writes of you, if he can tell

That you are you, so dignifies his story.

Let him but copy what in you is writ,

Not making worse what nature made so clear,

And such a counterpart shall fame his wit,

Making his style admired every where.

You to your beauteous blessings add a curse,

Being fond on praise, which makes your praises worse.

My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still,

While comments of your praise richly compiled,

Reserve thy character with golden quill,

And precious phrase by all the Muses filed.

I think good thoughts, whilst others write good words,

And like unlettered clerk still cry 'Amen'

To every hymn that able spirit affords,

In polished form of well-refined pen.

Hearing you praised, I say ''tis so, 'tis true,'

And to the most of praise add something more;

But that is in my thought, whose love to you,

Though words come hindmost, holds his rank before.

Then others, for the breath of words respect,

Me for my dumb thoughts, speaking in effect.

Was it the proud full sail of his great verse,

Bound for the prize of all too precious you,

That did my ripe thoughts in my brain inhearse,

Making their tomb the womb wherein they grew?

Was it his spirit, by spirits taught to write

Above a mortal pitch, that struck me dead?

No, neither he, nor his compeers by night

Giving him aid, my verse astonished.

He, nor that affable familiar ghost

Which nightly gulls him with intelligence,

As victors of my silence cannot boast;

I was not sick of any fear from thence:

But when your countenance filled up his line,

Then lacked I matter; that enfeebled mine.

Farewell! thou art too dear for my possessing,

And like enough thou know'st thy estimate,

The charter of thy worth gives thee releasing;

My bonds in thee are all determinate.

For how do I hold thee but by thy granting?

And for that riches where is my deserving?

The cause of this fair gift in me is wanting,

And so my patent back again is swerving.

Thy self thou gavest, thy own worth then not knowing,

Or me to whom thou gav'st it else mistaking;

So thy great gift, upon misprision growing,

Comes home again, on better judgement making.

Thus have I had thee, as a dream doth flatter,

In sleep a king, but waking no such matter.

When thou shalt be disposed to set me light,

And place my merit in the eye of scorn,

Upon thy side, against myself I'll fight,

And prove thee virtuous, though thou art forsworn.

With mine own weakness being best acquainted,

Upon thy part I can set down a story

Of faults concealed, wherein I am attainted;

That thou in losing me shalt win much glory:

And I by this will be a gainer too;

For bending all my loving thoughts on thee,

The injuries that to myself I do,

Doing thee vantage, double-vantage me.

Such is my love, to thee I so belong,

That for thy right, myself will bear all wrong.

Say that thou didst forsake me for some fault,

And I will comment upon that offence:

Speak of my lameness, and I straight will halt,

Against thy reasons making no defence.

Thou canst not, love, disgrace me half so ill,

To set a form upon desired change,

As I'll myself disgrace; knowing thy will,

I will acquaintance strangle, and look strange;

Be absent from thy walks; and in my tongue

Thy sweet beloved name no more shall dwell,

Lest I, too much profane, should do it wrong,

And haply of our old acquaintance tell.

For thee, against my self I'll vow debate,

For I must ne'er love him whom thou dost hate.

Then hate me when thou wilt; if ever, now;

Now, while the world is bent my deeds to cross,

Join with the spite of fortune, make me bow,

And do not drop in for an after-loss:

Ah! do not, when my heart hath 'scaped this sorrow,

Come in the rearward of a conquered woe;

Give not a windy night a rainy morrow,

To linger out a purposed overthrow.

If thou wilt leave me, do not leave me last,

When other petty griefs have done their spite,

But in the onset come: so shall I taste

At first the very worst of fortune's might;

And other strains of woe, which now seem woe,

Compared with loss of thee, will not seem so.

Some glory in their birth, some in their skill,

Some in their wealth, some in their body's force,

Some in their garments though new-fangled ill;

Some in their hawks and hounds, some in their horse;

And every humour hath his adjunct pleasure,

Wherein it finds a joy above the rest:

But these particulars are not my measure,

All these I better in one general best.

Thy love is better than high birth to me,

Richer than wealth, prouder than garments' cost,

Of more delight than hawks and horses be;

And having thee, of all men's pride I boast:

Wretched in this alone, that thou mayst take

All this away, and me most wretched make.

But do thy worst to steal thyself away,

For term of life thou art assured mine;

And life no longer than thy love will stay,

For it depends upon that love of thine.

Then need I not to fear the worst of wrongs,

When in the least of them my life hath end.

I see a better state to me belongs

Than that which on thy humour doth depend:

Thou canst not vex me with inconstant mind,

Since that my life on thy revolt doth lie.

O what a happy title do I find,

Happy to have thy love, happy to die!

But what's so blessed-fair that fears no blot?

Thou mayst be false, and yet I know it not.

So shall I live, supposing thou art true,

Like a deceived husband; so love's face

May still seem love to me, though altered new;

Thy looks with me, thy heart in other place:

For there can live no hatred in thine eye,

Therefore in that I cannot know thy change.

In many's looks, the false heart's history

Is writ in moods, and frowns, and wrinkles strange.

But heaven in thy creation did decree

That in thy face sweet love should ever dwell;

Whate'er thy thoughts, or thy heart's workings be,

Thy looks should nothing thence, but sweetness tell.

How like Eve's apple doth thy beauty grow,

If thy sweet virtue answer not thy show!

They that have power to hurt, and will do none,

That do not do the thing they most do show,

Who, moving others, are themselves as stone,

Unmoved, cold, and to temptation slow;

They rightly do inherit heaven's graces,

And husband nature's riches from expense;

They are the lords and owners of their faces,

Others, but stewards of their excellence.

The summer's flower is to the summer sweet,

Though to itself, it only live and die,

But if that flower with base infection meet,

The basest weed outbraves his dignity:

For sweetest things turn sourest by their deeds;

Lilies that fester, smell far worse than weeds.

How sweet and lovely dost thou make the shame

Which, like a canker in the fragrant rose,

Doth spot the beauty of thy budding name!

O! in what sweets dost thou thy sins enclose.

That tongue that tells the story of thy days,

Making lascivious comments on thy sport,

Cannot dispraise, but in a kind of praise;

Naming thy name blesses an ill report.

O! what a mansion have those vices got

Which for their habitation chose out thee,

Where beauty's veil doth cover every blot

And all things turns to fair that eyes can see!

Take heed, dear heart, of this large privilege;

The hardest knife ill-used doth lose his edge.

Some say thy fault is youth, some wantonness;

Some say thy grace is youth and gentle sport;

Both grace and faults are lov'd of more and less:

Thou mak'st faults graces that to thee resort.

As on the finger of a throned queen

The basest jewel will be well esteem'd,

So are those errors that in thee are seen

To truths translated, and for true things deem'd.

How many lambs might the stern wolf betray,

If like a lamb he could his looks translate!

How many gazers mightst thou lead away,

If thou wouldst use the strength of all thy state!

But do not so, I love thee in such sort,

As thou being mine, mine is thy good report.

How like a winter hath my absence been

From thee, the pleasure of the fleeting year!

What freezings have I felt, what dark days seen!

What old December's bareness everywhere!

And yet this time removed was summer's time;

The teeming autumn, big with rich increase,

Bearing the wanton burden of the prime,

Like widow'd wombs after their lords' decease:

Yet this abundant issue seemed to me

But hope of orphans, and unfathered fruit;

For summer and his pleasures wait on thee,

And, thou away, the very birds are mute:

Or, if they sing, 'tis with so dull a cheer,

That leaves look pale, dreading the winter's near.

From you have I been absent in the spring,

When proud pied April, dressed in all his trim,

Hath put a spirit of youth in every thing,

That heavy Saturn laughed and leapt with him.

Yet nor the lays of birds, nor the sweet smell

Of different flowers in odour and in hue,

Could make me any summer's story tell,

Or from their proud lap pluck them where they grew:

Nor did I wonder at the lily's white,

Nor praise the deep vermilion in the rose;

They were but sweet, but figures of delight,

Drawn after you, you pattern of all those.

Yet seemed it winter still, and you away,

As with your shadow I with these did play.

The forward violet thus did I chide:

Sweet thief, whence didst thou steal thy sweet that smells,

If not from my love's breath? The purple pride

Which on thy soft cheek for complexion dwells

In my love's veins thou hast too grossly dy'd.

The lily I condemned for thy hand,

And buds of marjoram had stol'n thy hair;

The roses fearfully on thorns did stand,

One blushing shame, another white despair;

A third, nor red nor white, had stol'n of both,

And to his robbery had annexed thy breath;

But, for his theft, in pride of all his growth

A vengeful canker eat him up to death.

More flowers I noted, yet I none could see,

Where art thou Muse that thou forget'st so long,

To speak of that which gives thee all thy might?

Spend'st thou thy fury on some worthless song,

Darkening thy power to lend base subjects light?

Return forgetful Muse, and straight redeem,

In gentle numbers time so idly spent;

Sing to the ear that doth thy lays esteem

And gives thy pen both skill and argument.

Rise, resty Muse, my love's sweet face survey,

If Time have any wrinkle graven there;

If any, be a satire to decay,

And make Time's spoils despised every where.

Give my love fame faster than Time wastes life,

So thou prevent'st his scythe and crooked knife.

O truant Muse what shall be thy amends

For thy neglect of truth in beauty dyed?

Both truth and beauty on my love depends;

So dost thou too, and therein dignified.

Make answer Muse: wilt thou not haply say,

'Truth needs no colour, with his colour fixed;

Beauty no pencil, beauty's truth to lay;

But best is best, if never intermixed'?

Because he needs no praise, wilt thou be dumb?

Excuse not silence so, for't lies in thee

To make him much outlive a gilded tomb

And to be praised of ages yet to be.

Then do thy office, Muse; I teach thee how

To make him seem, long hence, as he shows now.

My love is strengthened, though more weak in seeming;

I love not less, though less the show appear;

That love is merchandized, whose rich esteeming,

The owner's tongue doth publish every where.

Our love was new, and then but in the spring,

When I was wont to greet it with my lays;

As Philomel in summer's front doth sing,

And stops his pipe in growth of riper days:

Not that the summer is less pleasant now

Than when her mournful hymns did hush the night,

But that wild music burthens every bough,

And sweets grown common lose their dear delight.

Therefore like her, I sometime hold my tongue:

Because I would not dull you with my song.

Alack! what poverty my Muse brings forth,

That having such a scope to show her pride,

The argument all bare is of more worth

Than when it hath my added praise beside!

O! blame me not, if I no more can write!

Look in your glass, and there appears a face

That over-goes my blunt invention quite,

Dulling my lines, and doing me disgrace.

Were it not sinful then, striving to mend,

To mar the subject that before was well?

For to no other pass my verses tend

Than of your graces and your gifts to tell;

And more, much more, than in my verse can sit,

Your own glass shows you when you look in it.

To me, fair friend, you never can be old,

For as you were when first your eye I ey'd,

Such seems your beauty still. Three winters cold,

Have from the forests shook three summers' pride,

Three beauteous springs to yellow autumn turned,

In process of the seasons have I seen,

Three April perfumes in three hot Junes burned,

Since first I saw you fresh, which yet are green.

Ah! yet doth beauty like a dial-hand,

Steal from his figure, and no pace perceived;

So your sweet hue, which methinks still doth stand,

Hath motion, and mine eye may be deceived:

For fear of which, hear this thou age unbred:

Ere you were born was beauty's summer dead.

Let not my love be called idolatry,

Nor my beloved as an idol show,

Since all alike my songs and praises be

To one, of one, still such, and ever so.

Kind is my love to-day, to-morrow kind,

Still constant in a wondrous excellence;

Therefore my verse to constancy confined,

One thing expressing, leaves out difference.

Fair, kind, and true, is all my argument,

Fair, kind, and true, varying to other words;

And in this change is my invention spent,

Three themes in one, which wondrous scope affords.

Fair, kind, and true, have often lived alone,

Which three till now, never kept seat in one.

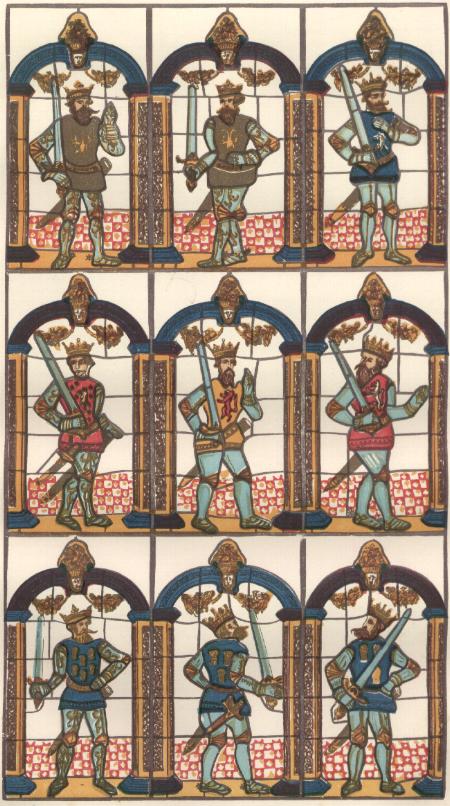

When in the chronicle of wasted time

I see descriptions of the fairest wights,

And beauty making beautiful old rhyme,

In praise of ladies dead and lovely knights,

Then, in the blazon of sweet beauty's best,

Of hand, of foot, of lip, of eye, of brow,

I see their antique pen would have expressed

Even such a beauty as you master now.

So all their praises are but prophecies

Of this our time, all you prefiguring;

And for they looked but with divining eyes,

They had not skill enough your worth to sing:

For we, which now behold these present days,

Have eyes to wonder, but lack tongues to praise.

Not mine own fears, nor the prophetic soul

Of the wide world dreaming on things to come,

Can yet the lease of my true love control,

Supposed as forfeit to a confined doom.

The mortal moon hath her eclipse endured,

And the sad augurs mock their own presage;

Incertainties now crown themselves assured,

And peace proclaims olives of endless age.

Now with the drops of this most balmy time,

My love looks fresh, and Death to me subscribes,

Since, spite of him, I'll live in this poor rhyme,

While he insults o'er dull and speechless tribes:

And thou in this shalt find thy monument,

When tyrants' crests and tombs of brass are spent.

What's in the brain that ink may character

Which hath not figured

to thee my true spirit?

What's new to speak, what now to register,

That may express my love, or thy dear merit?

Nothing, sweet boy; but yet, like prayers divine,

I must each day say o'er the very same;

Counting no old thing old, thou mine, I thine,

Even as when first I hallowed thy fair name.

So that eternal love in love's fresh case,

Weighs not the dust and injury of age,

Nor gives to necessary wrinkles place,

But makes antiquity for aye his page;

Finding the first conceit of love there bred,

Where time and outward form would show it dead.

O! never say that I was false of heart,

Though absence seemed my flame to qualify,

As easy might I from my self depart

As from my soul which in thy breast doth lie:

That is my home of love: if I have ranged,

Like him that travels, I return again;

Just to the time, not with the time exchanged,

So that myself bring water for my stain.

Never believe though in my nature reigned,

All frailties that besiege all kinds of blood,

That it could so preposterously be stained,

To leave for nothing all thy sum of good;

For nothing this wide universe I call,

Save thou, my rose, in it thou art my all.

Alas! 'tis true, I have gone here and there,

And made my self a motley to the view,

Gored mine own thoughts, sold cheap what is most dear,

Made old offences of affections new;

Most true it is, that I have looked on truth

Askance and strangely; but, by all above,

These blenches gave my heart another youth,

And worse essays proved thee my best of love.

Now all is done, have what shall have no end:

Mine appetite I never more will grind

On newer proof, to try an older friend,

A god in love, to whom I am confined.

Then give me welcome, next my heaven the best,

Even to thy pure and most most loving breast.

O! for my sake do you with Fortune chide,

The guilty goddess of my harmful deeds,

That did not better for my life provide

Than public means which public manners breeds.

Thence comes it that my name receives a brand,

And almost thence my nature is subdued

To what it works in, like the dyer's hand:

Pity me, then, and wish I were renewed;

Whilst, like a willing patient, I will drink

Potions of eisel 'gainst my strong infection;

No bitterness that I will bitter think,

Nor double penance, to correct correction.

Pity me then, dear friend, and I assure ye,

Even that your pity is enough to cure me.

Your love and pity doth the impression fill,

Which vulgar scandal stamped upon my brow;

For what care I who calls me well or ill,

So you o'er-green my bad, my good allow?

You are my all-the-world, and I must strive

To know my shames and praises from your tongue;

None else to me, nor I to none alive,

That my steeled sense or changes right or wrong.

In so profound abysm I throw all care

Of others' voices, that my adder's sense

To critic and to flatterer stopped are.

Mark how with my neglect I do dispense:

You are so strongly in my purpose bred,

That all the world besides methinks y'are dead.

Since I left you, mine eye is in my mind;

And that which governs

me to go about

Doth part his function and is partly blind,

Seems seeing, but effectually is out;

For it no form delivers to the heart

Of bird, of flower, or shape which it doth latch:

Of his quick objects hath the mind no part,

Nor his own vision holds what it doth catch;

For if it see the rud'st or gentlest sight,

The most sweet favour or deformed'st creature,

The mountain or the sea, the day or night,

The crow, or dove, it shapes them to your feature.

Incapable of more, replete with you,

My most true mind thus maketh mine eye untrue.

Or whether doth my mind, being crowned with you,

Drink up the monarch's plague, this flattery?

Or whether shall I say, mine eye saith true,

And that your love taught it this alchemy,

To make of monsters and things indigest

Such cherubins as your sweet self resemble,

Creating every bad a perfect best,

As fast as objects to his beams assemble?

O! 'tis the first, 'tis flattery in my seeing,

And my great mind most kingly drinks it up:

Mine eye well knows what with his gust is 'greeing,

And to his palate doth prepare the cup:

If it be poisoned, 'tis the lesser sin

That mine eye loves it and doth first begin.

Those lines that I before have writ do lie,

Even those that said I could not love you dearer:

Yet then my judgment knew no reason why

My most full flame should afterwards burn clearer.

But reckoning Time, whose million'd accidents

Creep in 'twixt vows, and change decrees of kings,

Tan sacred beauty, blunt the sharp'st intents,

Divert strong minds to the course of altering things;

Alas! why, fearing of Time's tyranny,

Might I not then say, 'Now I love you best,'

When I was certain o'er incertainty,

Crowning the present, doubting of the rest?

Love is a babe, then might I not say so,

To give full growth to that which still doth grow?

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove:

O, no! it is an ever-fixed mark,

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wandering bark,

Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken.

Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle's compass come;

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

Accuse me thus: that I have scanted all,

Wherein I should your great deserts repay,

Forgot upon your dearest love to call,

Whereto all bonds do tie me day by day;

That I have frequent been with unknown minds,

And given to time your own dear-purchased right;

That I have hoisted sail to all the winds

Which should transport me farthest from your sight.

Book both my wilfulness and errors down,

And on just proof surmise accumulate;

Bring me within the level of your frown,

But shoot not at me in your wakened hate;

Since my appeal says I did strive to prove

The constancy and virtue of your love.

Like as, to make our appetites more keen,

With eager compounds we our palate urge;

As, to prevent our maladies unseen,

We sicken to shun sickness when we purge;

Even so, being full of your ne'er-cloying sweetness,

To bitter sauces did I frame my feeding;

And, sick of welfare, found a kind of meetness

To be diseased, ere that there was true needing.

Thus policy in love, to anticipate

The ills that were not, grew to faults assured,

And brought to medicine a healthful state

Which, rank of goodness, would by ill be cured;

But thence I learn and find the lesson true,

Drugs poison him that so fell sick of you.

What potions have I drunk of Siren tears,

Distilled from limbecks foul as hell within,

Applying fears to hopes, and hopes to fears,

Still losing when I saw myself to win!

What wretched errors hath my heart committed,

Whilst it hath thought itself so blessed never!

How have mine eyes out of their spheres been fitted,

In the distraction of this madding fever!

O benefit of ill! now I find true

That better is by evil still made better;

And ruined love, when it is built anew,

Grows fairer than at first, more strong, far greater.

So I return rebuked to my content,

And gain by ills thrice more than I have spent.

That you were once unkind befriends me now,

And for that sorrow, which I then did feel,

Needs must I under my transgression bow,

Unless my nerves were brass or hammered steel.

For if you were by my unkindness shaken,

As I by yours, you've passed a hell of time;

And I, a tyrant, have no leisure taken

To weigh how once I suffered in your crime.

O! that our night of woe might have remembered

My deepest sense, how hard true sorrow hits,

And soon to you, as you to me, then tendered

The humble salve, which wounded bosoms fits!

But that your trespass now becomes a fee;

Mine ransoms yours, and yours must ransom me.

'Tis better to be vile than vile esteemed,

When not to be receives reproach of being;

And the just pleasure lost, which is so deemed

Not by our feeling, but by others' seeing:

For why should others' false adulterate eyes

Give salutation to my sportive blood?

Or on my frailties why are frailer spies,

Which in their wills count bad what I think good?

No, I am that I am, and they that level

At my abuses reckon up their own:

I may be straight though they themselves be bevel;

By their rank thoughts, my deeds must not be shown;

Unless this general evil they maintain,

All men are bad and in their badness reign.

Thy gift, thy tables, are within my brain

Full charactered with lasting memory,

Which shall above that idle rank remain,

Beyond all date, even to eternity:

Or, at the least, so long as brain and heart

Have faculty by nature to subsist;

Till each to razed oblivion yield his part

Of thee, thy record never can be missed.

That poor retention could not so much hold,

Nor need I tallies thy dear love to score;

Therefore to give them from me was I bold,

To trust those tables that receive thee more:

To keep an adjunct to remember thee

Were to import forgetfulness in me.

No, Time, thou shalt not boast that I do change:

Thy pyramids built up with newer might

To me are nothing novel, nothing strange;

They are but dressings of a former sight.

Our dates are brief, and therefore we admire

What thou dost foist upon us that is old;

And rather make them born to our desire

Than think that we before have heard them told.

Thy registers and thee I both defy,

Not wondering at the present nor the past,

For thy records and what we see doth lie,

Made more or less by thy continual haste.

This I do vow and this shall ever be;

I will be true despite thy scythe and thee.

If my dear love were but the child of state,

It might for Fortune's bastard be unfathered,

As subject to Time's love or to Time's hate,

Weeds among weeds, or flowers with flowers gathered.

No, it was builded far from accident;

It suffers not in smiling pomp, nor falls

Under the blow of thralled discontent,

Whereto th' inviting time our fashion calls:

It fears not policy, that heretic,

Which works on leases of short-number'd hours,

But all alone stands hugely politic,

That it nor grows with heat, nor drowns with showers.

To this I witness call the fools of time,

Which die for goodness, who have lived for crime.

Were't aught to me I bore the canopy,

With my extern the outward honouring,

Or laid great bases for eternity,

Which proves more short than waste or ruining?

Have I not seen dwellers on form and favour

Lose all and more by paying too much rent

For compound sweet, forgoing simple savour,

Pitiful thrivers, in their gazing spent?

No; let me be obsequious in thy heart,

And take thou my oblation, poor but free,

Which is not mixed with seconds, knows no art,

But mutual render, only me for thee.

Hence, thou suborned informer! a true soul

When most impeached stands least in thy control.

O thou, my lovely boy, who in thy power

Dost hold Time's fickle glass, his sickle,

hour;

Who hast by waning grown, and therein showest

Thy lovers withering, as thy sweet self growest.

If Nature, sovereign mistress over wrack,

As thou goest onwards still will pluck thee back,

She keeps thee to this purpose, that her skill

May time disgrace and wretched minutes kill.

Yet fear her, O thou minion of her pleasure!

She may detain, but not still keep, her treasure:

Her audit (though delayed) answered must be,

And her quietus is to render thee.

( )

( )

In the old age black was not counted fair,

Or if it were, it bore not beauty's name;

But now is black beauty's successive heir,

And beauty slandered with a bastard shame:

For since each hand hath put on Nature's power,

Fairing the foul with Art's false borrowed face,

Sweet beauty hath no name, no holy bower,

But is profaned, if not lives in disgrace.

Therefore my mistress' eyes are raven black,

Her eyes so suited, and they mourners seem

At such who, not born fair, no beauty lack,

Sland'ring creation with a false esteem:

Yet so they mourn becoming of their woe,

That every tongue says beauty should look so.

How oft when thou, my music, music play'st,

Upon that blessed wood whose motion sounds

With thy sweet fingers when thou gently sway'st

The wiry concord that mine ear confounds,

Do I envy those jacks that nimble leap,

To kiss the tender inward of thy hand,

Whilst my poor lips which should that harvest reap,

At the wood's boldness by thee blushing stand!

To be so tickled, they would change their state

And situation with those dancing chips,

O'er whom thy fingers walk with gentle gait,

Making dead wood more bless'd than living lips.

Since saucy jacks so happy are in this,

Give them thy fingers, me thy lips to kiss.

The expense of spirit in a waste of shame

Is lust in action: and till action, lust

Is perjured, murderous, bloody, full of blame,

Savage, extreme, rude, cruel, not to trust;

Enjoyed no sooner but despised straight;

Past reason hunted; and no sooner had,

Past reason hated, as a swallowed bait,

On purpose laid to make the taker mad.

Mad in pursuit and in possession so;

Had, having, and in quest to have extreme;

A bliss in proof, and proved, a very woe;

Before, a joy proposed; behind a dream.

All this the world well knows; yet none knows well

To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.

My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red, than her lips red:

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

I grant I never saw a goddess go,

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground:

And yet by heaven, I think my love as rare,

As any she belied with false compare.

Thou art as tyrannous, so as thou art,

As those whose beauties proudly make them cruel;

For well thou know'st to my dear doting heart

Thou art the fairest and most precious jewel.

Yet, in good faith, some say that thee behold,

Thy face hath not the power to make love groan;

To say they err I dare not be so bold,

Although I swear it to myself alone.

And to be sure that is not false I swear,

A thousand groans, but thinking on thy face,

One on another's neck, do witness bear

Thy black is fairest in my judgment's place.

In nothing art thou black save in thy deeds,

And thence this slander, as I think, proceeds.

Thine eyes I love, and they, as pitying me,

Knowing thy heart torments me with disdain,

Have put on black and loving mourners be,

Looking with pretty ruth upon my pain.

And truly not the morning sun of heaven

Better becomes the grey cheeks of the east,